F1 2026 Power Units: Hybrid Split and Sustainable Fuel

As the 2026 Formula 1 season begins, the sport is stepping into its biggest change so far. The main question is how the new power units keep F1 fast and exciting while making a serious move toward lower emissions.

The answer is a 50/50 split between the internal combustion engine and a huge jump in electric power, running on 100% advanced sustainable fuel. With electric output rising from 120kW to 350kW and the removal of the MGU-H, F1 now has a package that links closely to road cars while still thrilling the drivers.

This is more than a rule tweak; it is a complete rethink of what an F1 car is. As of January 9, 2026, we are seeing the first real cars built around these new "Nimble Car" ideas. The targets are clear: closer racing, a smaller carbon footprint, and keeping the top level of motorsport as the best test bed for new car technology.

F1 2026 Power Units: Key Changes and Innovations

Why Is Formula 1 Changing Power Unit Regulations in 2026?

Formula 1 has always pushed new technology, but the 2026 rules come from two main needs: lower emissions and fairer competition. The previous engines were the most efficient in F1 history, but they were very complex. The MGU-H in particular made it hard and expensive for new engine makers to join.

By simplifying the layout and greatly increasing electric power, F1 is now more attractive to big car companies that are moving toward electric road cars.

These changes also support F1’s "Net Zero by 2030" plan. Using fully sustainable fuels and smarter energy use keeps the sport relevant in a world that cares more and more about climate impact. The rules are meant to show that a high-performance engine can work with a cleaner future if the fuel and energy recovery systems are advanced enough.

Which Engine Manufacturers Are Joining F1 in 2026?

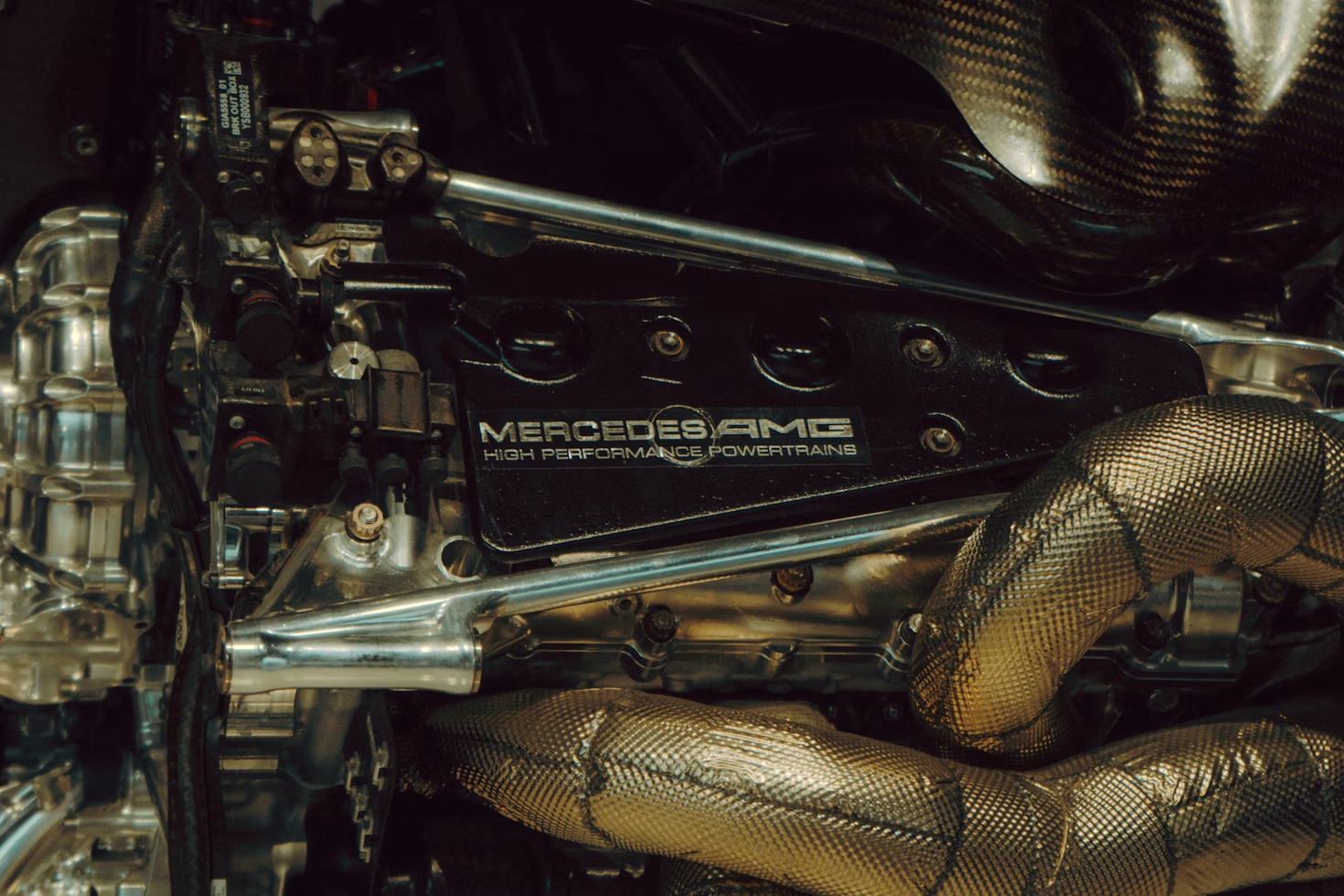

The 2026 rules have sparked strong interest from manufacturers. The grid now mixes long-term names with new faces. Ferrari and Mercedes stay in the sport, while Honda has officially returned and is now working with Aston Martin after a short break. This comeback shows how the new rules solved the earlier complexity problems that discouraged long stays.

On top of that, Audi joins F1 as a power unit maker for the first time, and Red Bull Powertrains has formed a partnership with Ford. Cadillac is also entering as a constructor, starting with Ferrari engines and aiming for a General Motors-built power unit by 2029.

This wave of new and returning brands is a direct result of the FIA’s move to simpler hybrid parts and a stronger financial rule set.

Hybrid Split: Balancing Internal Combustion and Electric Power

How Will the 50/50 Hybrid Split Work?

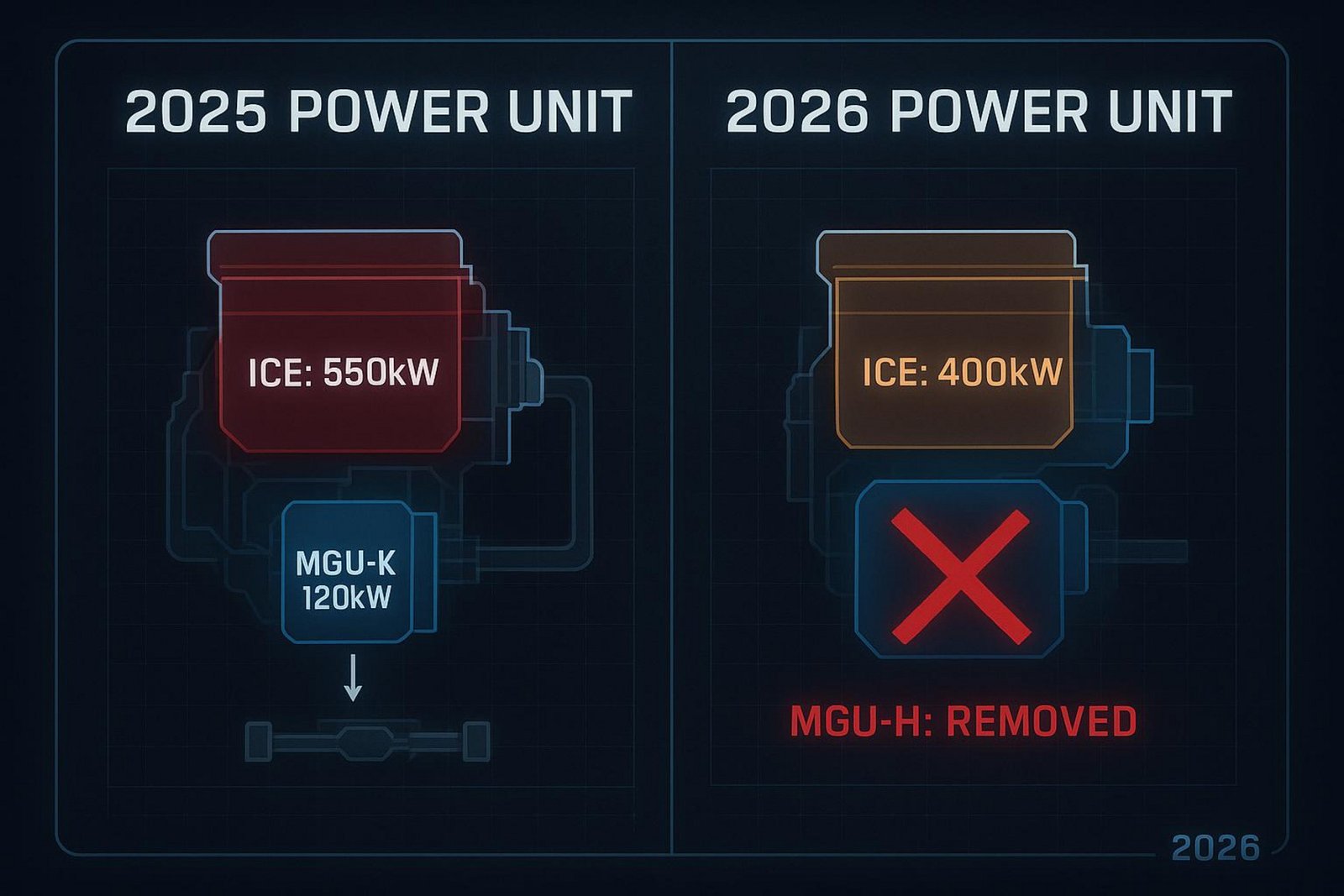

The standout figure for 2026 is the near 50/50 balance between the internal combustion engine (ICE) and electric power. In the past, the ICE provided about 80% of the total output, with the hybrid system adding only a small part. Now, the electric motor (MGU-K) output has tripled, going from 120kW to 350kW.

This means performance is no longer driven mostly by fuel flow. The key factor is now how the battery and engine work together. On long straights, the car will use a lot of stored electric energy, so energy management becomes a key part of racing. Drivers must think carefully about where to use electric power and where to recover it.

What Is the Role of the Internal Combustion Engine in 2026?

Even with the growth in electric power, the 1.6-litre V6 turbo hybrid engine is still the core of the car. But its job has changed from being mainly a power source to being a very efficient energy maker.

To make room for the extra electric power, the ICE’s peak output has been reduced from about 550kW to around 400kW, with fuel flow cut from 100kg/hr to about 75kg/hr.

Engineers now focus on thermal efficiency above everything else. With limited fuel flow, the only way to gain an advantage is to get more work out of each unit of sustainable fuel. The ICE becomes a key part of the overall energy loop, working closely with the hybrid system so the battery stays charged over a full race.

What Will Replace MGU-H in the New Power Units?

In a move that many did not expect but manufacturers welcomed, the MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit - Heat) has been removed for 2026. The MGU-H was a clever device that recovered energy from exhaust gases and removed turbo lag, but it was expensive, heavy, and not very useful for normal road cars.

Instead of adding a new part, the FIA has put all energy recovery duties on the MGU-K and the ICE. Without the MGU-H, the power unit is simpler, lighter, and easier to fit inside the tighter "Nimble Car" chassis.

This cleaner layout helped convince brands like Audi and Ford that they could join F1 and have a fair shot at being competitive.

How Will MGU-K Contribute to Performance?

The MGU-K (Motor Generator Unit - Kinetic) becomes the star of the 2026 hybrid package. At 350kW-about 469 horsepower-it now supplies nearly half of the car’s total peak power. This big boost in electric torque gives strong acceleration out of slow corners, helping to make up for the lower ICE power.

But this also brings new challenges. The MGU-K must both deliver power and recover energy under braking. Because electric demand is so high under the 2026 rules, the MGU-K has to be more efficient than ever. Designers are working on ways to raise power density while keeping the weight under control.

How Much Energy Will Be Recovered Through Braking?

Energy recovery improves a lot in 2026, with cars able to collect about twice as much energy per lap as before. Teams expect to harvest around 8.5 to 9 megajoules (MJ) every lap through the Energy Recovery System (ERS). Most of this comes from stronger regenerative braking and "lifting and coasting" at the end of long straights.

This extra recovery is needed because a 350kW MGU-K would empty a normal battery very quickly without steady input. Drivers and race engineers now work with different "Recharge Modes" to manage state of charge, saving enough energy for key overtakes or to defend in important parts of the lap.

What Is Manual Override Mode and How Does It Affect Racing?

To make on-track battles more exciting, the 2026 rules bring in "Manual Override Mode," commonly called the Boost button. It takes over the role that DRS (Drag Reduction System) had as the main tool for overtaking. When a driver is within one second of the car in front at a set detection point, they gain access to an extra 0.5MJ of electric energy.

The strength of this system is in how it can be used. While the leading car’s energy use starts to drop off after 290km/h, the chasing car can use override to keep the full 350kW up to 337km/h. This creates a clear speed difference and rewards the driver who can stay close through the corners. The extra energy can be used in one big hit or spread across the lap to keep pressure on the rival.

Sustainable Fuel: Formula 1’s Commitment to Greener Racing

What Makes the 2026 Fuel Sustainable?

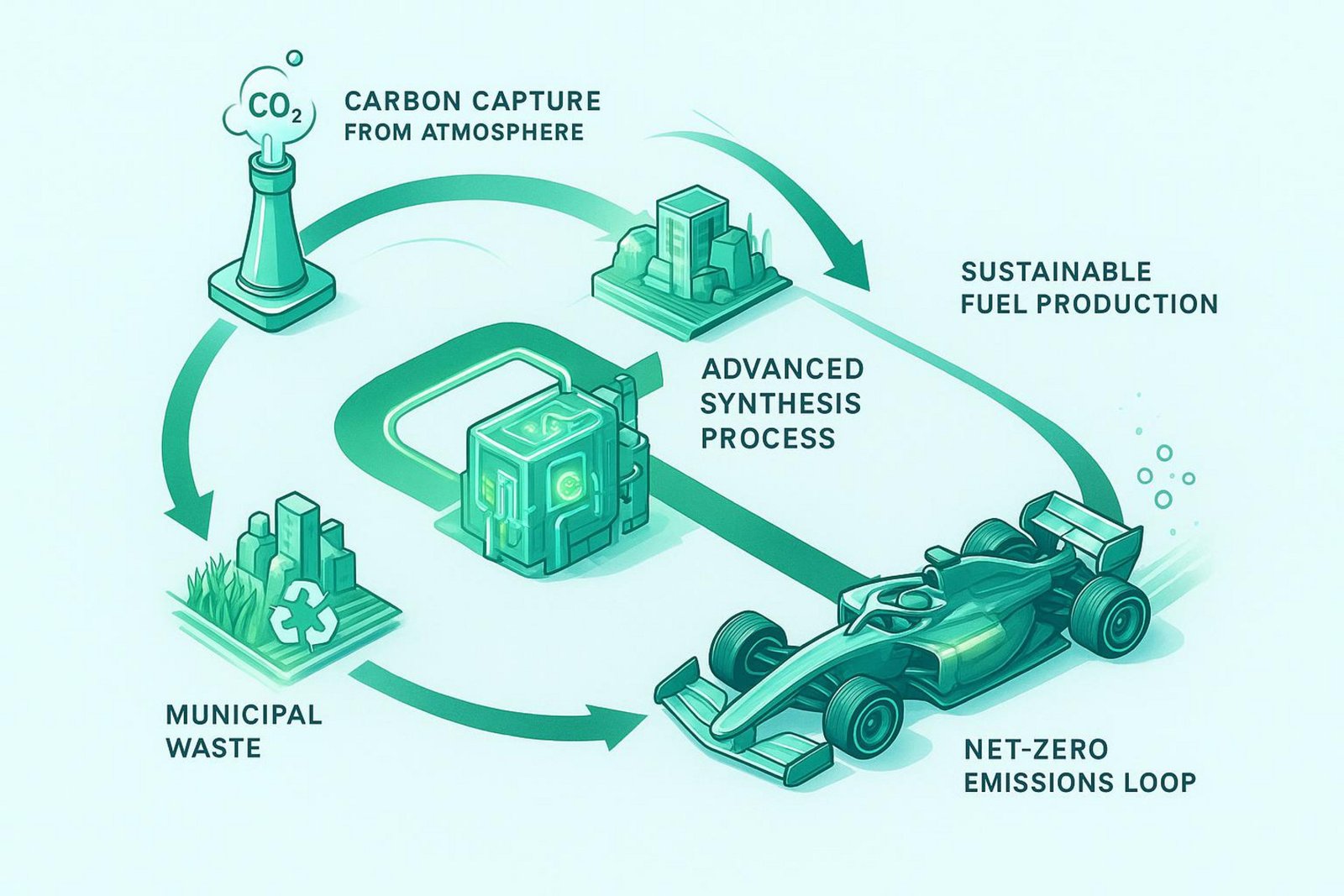

For the first time, every car on the F1 grid runs on 100% Advanced Sustainable Fuel. These are "drop-in" fuels made from non-fossil sources, not standard biofuels. Main sources include carbon capture (taking CO2 from the air), municipal waste, and non-food biomass. This avoids using land needed for food or driving deforestation.

To keep the fuel honest, the FIA has set up the Sustainable Racing Fuel Assurance Scheme (SRFAS). Independent checks track each batch from source to engine. The aim is a fuel that does not add any new fossil carbon to the air when burned, turning the ICE into part of the solution instead of part of the problem.

How Does Alternative Fuel Impact Performance and Emissions?

The move to sustainable fuel is a quiet battle of chemistry. These fuels must match or come close to the performance of normal fossil fuels, but they behave differently inside the engine. They can have different volatility and burn speeds.

When blended correctly, though, they still let the 2026 power units reach more than 700kW total peak power, showing that cleaner fuel does not have to slow the cars down.

On emissions, the effect is large. By using captured carbon and waste streams, F1 is showing how a circular carbon cycle can work. These "drop-in" fuels also work with current fuel systems and engines, so the tech developed in F1 could later cut emissions from the 1.2 billion internal combustion vehicles expected to be on the road by 2030.

What Are the Challenges of Moving to Sustainable Fuel?

Fuel partners like PETRONAS and Aramco face a main problem: many sustainable feedstocks have lower energy density than fossil fuels. Oil-based fuels became standard because they are very energy-rich and stable. Sustainable sources can add impurities or burn more slowly, which would hurt thermal efficiency in a highly stressed race engine.

Cost is another problem. Making these fuels at large scale and at the tight quality level that F1 needs is much more expensive than refining crude oil.

Mercedes boss Toto Wolff has said the supply chain for "green" inputs is more complex than first expected, needing big investment in gasification and Fischer-Tropsch processes to create fuel good enough for racing.

How Is Energy Density Balanced with Sustainability?

Balancing energy density and sustainability is a careful job at the molecular level. Suppliers use methods like hydroprocessing to strip oxygen and sulfur from feedstocks and produce clean hydrocarbons that behave like fossil petrol. The aim is to create a non-fossil molecule that acts like a fossil one inside the engine.

Because the 2026 rules focus on energy flow instead of simple fuel-flow limits, any drop in energy content immediately costs performance. This has triggered a "chemistry arms race" in labs worldwide, where suppliers chase purity and stability just as hard as they used to chase octane. A fuel that burns slightly hotter or more steadily can change the whole engine setup and could even decide a championship.

Technical and Competitive Impacts of the 2026 Power Units

How Will Reduced Fuel Flow Affect Race Strategy?

Cutting fuel flow to 75kg/hr changes how teams plan races. In the past, drivers could often run near full fuel flow for long periods. In 2026, efficiency becomes the main weapon. Strategy now centers on "energy management cycles," where drivers juggle fuel use and battery charge.

We are likely to see a wider range of tactics, with some teams using short, intense power bursts followed by strong harvesting phases. Lower fuel flow also makes running behind another car more painful; a driver stuck in dirty air cannot just use extra fuel to pass. They must work with hybrid tools and aero settings to find chances, turning the race into more of a mental game as well as a physical one.

What Is the Expected Performance Gain from Hybrid Systems?

Early on, many thought lap times might be slightly slower because of heavier batteries and lower ICE power. But the hybrid gains are very large. The extra 120 horsepower from the MGU-K means strong drive out of corners. When combined with new "Active Aero" that cuts drag on the straights, the 2026 cars should reach higher top speeds than before.

The bigger benefit comes from how drivers can use energy. With three times the electric braking power and more ways to harvest, they can plan where to deploy. They might save energy for one sector where their car is strong, making performance over a lap more varied and harder to predict.

How Will the New Regulations Affect Team Competition?

The 2026 rules aim to bring the field closer and put more focus on driver skill and smart engineering. By dropping the complex MGU-H and moving to a 50/50 hybrid split, the FIA has cut the knowledge gap that let some makers lead for long periods. New rules for flatter floors and simpler wings also reduce extreme downforce, helping cars follow each other more easily in corners.

Mercedes Deputy Technical Director Simone Resta has said that racing in 2026 should be "unpredictable." With more manufacturers, stricter limits on turbulent air, and more tools for attack and defence, the running order is likely to change. The teams that best join together sustainable fuel, battery use, and active aero are the ones most likely to run at the front in this new era.

Away from engines and fuel, the 2026 rules also bring tougher safety standards that often get less attention than kilowatts and carbon capture. The survival cell now faces harsher tests, and the roll hoop must take a 20G load-around the weight of nine family cars. A new two-stage front crash structure has also been added to give better protection in secondary hits, learned directly from recent big accidents.

These changes, plus the "Nimble Car" idea that makes cars 30kg lighter and 100mm narrower, mean that 2026 is not just about being cleaner and faster-it is also about being smarter and safer for the drivers at the center of the sport.