F1 Active Aero 2026: How It Changes Overtakes, Strategy

Formula 1’s 2026 rules bring the biggest technical shake-up the sport has ever seen. They change how drivers overtake and plan races by replacing the old Drag Reduction System (DRS) with a new “Active Aero” approach. Instead of a simple “open or closed” rear wing like DRS, Active Aero lets drivers keep adjusting both front and rear wings to balance grip and straight-line speed.

Combined with a big jump in electric power and new tools like “Overtake Mode” and “Boost Mode,” F1 is moving away from easy, push-button passes and into a high-pressure game of energy use, where the winner is often the driver who thinks best in real time.

As of early January 2026, just weeks before the first private tests in Barcelona, teams are buzzing. The cars are smaller, lighter, and more agile, but the key change is how they move through the air. By separating drag reduction from the old one-second DRS rule, F1 has turned aero efficiency into a standard part of each lap.

Overtaking now grows out of how well a driver manages electrical energy and recovery, not just how close they are to the car in front.

What Is F1 Active Aero in 2026?

In 2026, Active Aerodynamics means the car can change its wing shapes while running on track. For the first time, both the front and rear wings have moving parts that can switch between two main positions. It’s more than a flap flipping up on a straight; it is a basic shift in how the car’s downforce is balanced to match either a tight corner or a high-speed stretch.

This system exists to match the new 2026 power units, which now deliver about half their power from the engine and half from electric systems. Because these engines give less “natural” top speed than before, the cars must create far less drag on the straights to keep lap times up. With smaller cars and these moving aero parts, F1 has cut overall drag by up to 40%.

Key Features of Active Aerodynamics

The system has two main states: Corner Mode and Straight Mode.

- Corner Mode is the default. Here, the front and rear wing flaps are “closed” to give maximum downforce and grip for twisty parts of the lap.

- When a driver reaches a marked activation zone on a straight, they can switch to Straight Mode. In this position, the flaps on both wings “open” or flatten, cutting drag sharply and letting the car reach far higher top speeds than with a fixed wing.

The 2026 chassis is about 30kg lighter and the wheelbase is shorter by 200mm, now 3,400mm. This smaller car, along with a 15-30% drop in total downforce due to the removal of ground-effect tunnels, makes the cars livelier and harder to control at the limit.

The Active Aero system is like the “control center” that helps drivers handle this sharpness, giving them grip when they need it and low drag when they don’t.

How Active Aero Differs from Previous DRS Systems

The biggest change from DRS is that Active Aero is no longer an overtaking aid only for the chasing car. Under DRS, you had to be within one second of the car ahead to open the rear wing. In 2026, every driver can use Straight Mode in the set zones, no matter where they are on track or how close they are to another car. It is now a standard lap-time tool, not a “pass button.”

This responds to long-running criticism that DRS made passing feel “fake.” By giving everyone drag reduction, the FIA has moved the main overtake help from the wings to the power unit.

All cars enjoy low drag on the straights, but making a pass now depends on how well a driver uses extra energy. Position fights become more about smart energy use than about who presses a flap at the right time.

How Does Active Aero Affect Overtaking in F1?

With the old “DRS pass” gone, overtaking in 2026 is a richer puzzle. Because the car in front can also cut drag on the straights, the driver behind can’t just rely on having a clear top-speed edge. The focus shifts to Overtake Mode-an advanced energy override that gives the chasing car extra power for a short time.

This turns battles into a cat-and-mouse contest. A driver may sit close for several laps, not to open a flap, but to charge the battery and set up one big Overtake Mode attack. The lack of ground-effect tunnels also means the cars disturb the air less, so they can follow more closely in corners without losing front grip. That opens overtaking chances in places that used to be “single-file only.”

Overtake Modes: What Changes for Drivers?

For drivers, the steering wheel has become a tactical dashboard. The new Overtake Mode is the main passing tool, replacing the old DRS one-second rule. When a driver is within one second of the car ahead at the detection point (often the last corner), they gain the right to use an extra 0.5MJ of energy on the next lap. This is more than a brief burst; it changes the power curve, letting them hold maximum electric power for longer.

This mode is very strategic. Unlike DRS, which only worked in fixed zones, the energy from Overtake Mode can be spread around the lap or used in one big hit on a long straight. Drivers must choose whether to spend it closing a gap through a twisty sector or saving it for a powerful run onto a main straight. The responsibility for timing the move sits firmly with the driver again.

Comparing Active Aero vs. DRS Overtake Assistance

Moving from DRS to Active Aero and Overtake Mode changes things from a simple on/off setup to a variable one. DRS was either active or not.

By contrast, the 2026 rules allow “partial aero modes” in wet or tricky conditions-for example, the front wing in Straight Mode while the rear stays in Corner Mode. That gives a level of fine-tuning we haven’t seen before. Overtake help now comes from how you use energy, not just from aero angles.

DRS often created easy “highway passes,” where the car behind would blast by long before the braking zone. The 2026 system tries to create more side-by-side fights. Because the lead car also has low drag, the speed boost from Overtake Mode is tuned to get the cars roughly level at the braking point. That pushes drivers to out-brake each other and show real racecraft to finish the move.

Speed Differences and Energy Management

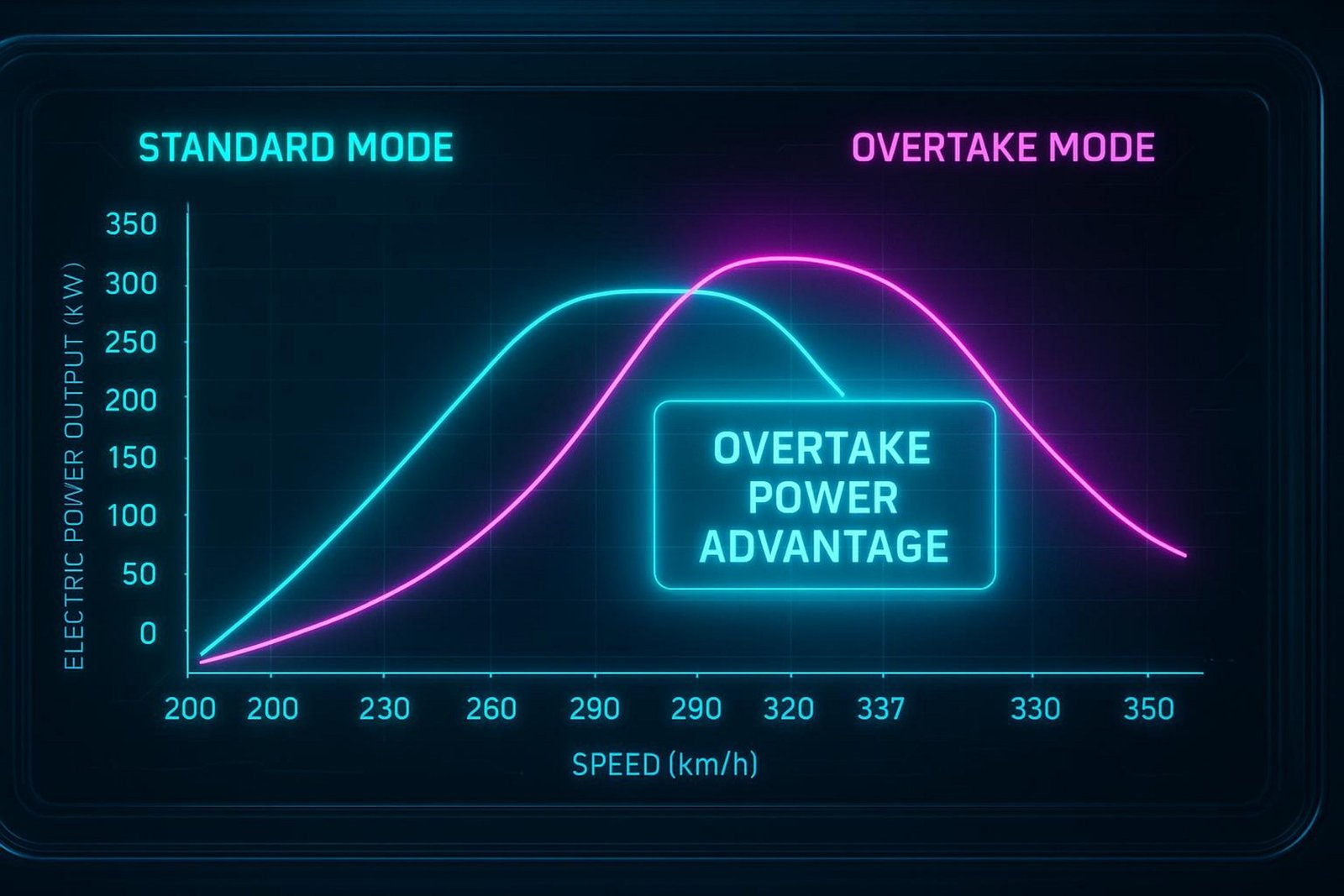

The new rules set a clear “rampdown” for energy use. In normal running, a car’s electric boost starts to fade once it reaches 290km/h. But a car in Overtake Mode can keep using the full 350kW of power all the way up to 337km/h. This gives a strong “closing speed” in the final part of the straight, even when both cars have their wings open.

This speed gap is the new fight zone. Drivers must watch their State of Charge (SoC) all the time. If the car in front burns too much energy defending on lap 10, it might start “clipping” (running out of electric power) early on the straights on lap 11. Then it becomes an easy target for a rival who has saved energy and charged up properly.

Boost Mode and Overtake Button Functions

On top of the one-second-based Overtake Mode, drivers also have a Boost Mode button. This is similar to “push-to-pass” seen in other series, but built into a more powerful hybrid system.

Boost Mode gives full engine and battery output anywhere on the track, no matter how close other cars are. It can be used to break away from a pursuer or to block an attack.

The downside is that Boost Mode eats up the battery quickly. It is a limited resource that needs planning. Expect drivers to “save” their boost for key moments-such as the final few laps or a vital “overcut” push lap around pit stops. The button on the wheel connects the driver’s thumb directly to the car’s 350kW MGU-K.

Recharge Requirements and Their Influence on Strategy

To use power, you need to collect it first. Recharge is now a visible, central part of race strategy. In 2026, energy comes not only from normal braking but also from “super clipping” at the end of straights and from “lift-and-coast” driving. The ECU manages most of this automatically, but drivers can manually choose “lift-off regen” modes to focus on charging the battery instead of pure lap time.

This creates a clear rhythm. A driver might spend two laps recharging-accepting a loss of a few tenths-to fill the battery for a longer attack later. Strategy goes beyond tires and fuel and becomes an “energy cycle” problem. Teams will calculate the best “recharge-to-boost” balance for each track, from the flat-out straights of Monza to the tight streets of Monaco.

Strategic Implications of Active Aero in Race Tactics

Under the 2026 rules, every driver becomes part race engineer. Strategy no longer lives only on the pit wall; it also lives inside the cockpit. With MGU-K power rising from 120kW to 350kW, running out of energy now hurts much more than before. A car that harvests at the wrong point on the lap might lose several places in one sector.

The cars are also 100mm narrower and use slimmer tires, which makes it a bit easier to fight for space on track. On tight circuits like Monaco, that extra room can be the difference between a deadlock and a brave move up the inside. Grid position will still matter a lot, but race-long energy control could now be the main leveler between cars.

Energy Recuperation and Deployment During Races

Energy recovery is at the core of a 2026 race. With the MGU-H (turbo heat recovery) gone, the MGU-K has to do all the work. Braking zones are now the key “fuel stops” for electric power. Drivers who brake late gain time and can also pick up more energy-if their systems can cope with the extra torque and load.

Spending that energy is just as important. Teams will run detailed engine maps to decide where to use the 350kW best. At Spa, they might focus on the run through Eau Rouge and up the Kemmel Straight. On a street track, plans may lean toward short bursts to get better traction out of slow corners.

Driver Decision-Making: When to Use Overtake Mode

The one-second Overtake Mode window acts as a trigger for attack. But just having the option doesn’t mean a driver should press it right away. A smart racer might wait until they are fully in the slipstream of the car ahead before using the mode, stacking the slipstream effect with the electric boost for maximum impact.

There is also room for “dummy” plays. A driver could turn on Overtake Mode early in a lap to scare the rival into burning their own Boost in defense, then back off and save the real attack for later. When the defender’s battery is lower, the attacker can move in for a cleaner shot. This mental game is exactly the kind of battle the FIA wants these rules to create.

Balancing Speed and Battery Management

Every 2026 driver’s target is simple: reach the end of the straight without the car “derating” (cutting power because the battery is empty). Getting there is not simple at all. If a driver pushes too hard early in the lap, the car may be weak later where it matters most. Engineers will often talk about “State of Charge targets,” telling drivers when to save and when to spend.

Active Aero complicates this balance. Opening the wings lowers drag and engine load, which also changes how and where energy is recovered and used. The mix of Straight Mode and Boost Mode is the sweet spot that teams like Mercedes, Ferrari, Audi, and Red Bull Ford are fine-tuning in their simulators right now.

Potential Risks and Controversies

A rule change this big will bring problems along the way. FIA single-seater director Nikolas Tombazis has already said some parts of the rules are “levers” the FIA may adjust. There is a thin line between “great racing” and “too easy.” If Overtake Mode is too strong, we may see something like the old “DRS trains” or the opposite: constant, effortless lead swaps where drivers can’t defend.

There is also the issue of “velocity profile.” The FIA wants the cars to look natural on track. They want to avoid strange visuals, such as a car suddenly slowing mid-straight because it has run out of electric power. Keeping the cars looking fast and smooth is key for how the racing looks to fans.

Risks of Unintended Consequences or Competitive Disparity

The biggest problem area may be the political fight between power unit manufacturers. With five engine makers (including new ones like Audi and Red Bull Ford) serving eleven teams, the gap in energy control software could be large. If one engine company finds a special trick to recover more energy during “super clipping,” they could dominate in a way Active Aero can’t correct.

Another risk is new and odd passing zones. Some team bosses expect overtakes in corners where we’ve never seen them before. Others worry that once teams find the best energy plan for each track, the racing might become too stable and predictable.

The FIA has kept the option to change track-specific limits-such as maximum energy recovery-after winter testing if one team or engine seems to have too big an edge.

What Could F1's 2026 Active Aero Era Mean for the Championship?

The 2026 season is a reset for the running order. By shrinking the cars and leaning into driver-controlled energy strategy, F1 is trying to move away from a decade where engineers and data heavily shaped who won.

The smaller cars answer fan complaints about huge “land yachts” that didn’t fit classic tracks. Lighter, sharper cars that are harder to handle at the limit should bring driving skill back to the center of the title fight.

The arrival of Audi and the Red Bull-Ford tie-up adds extra interest among manufacturers. These newcomers step into a championship where the basic rules of how you race have changed. Winning in 2026 won’t just be about having the most downforce; it will go to the team that builds the best “energy machine.” For fans, that means less certainty. The form book is gone, and each race weekend could turn into either a clever tactical contest or a wild battle to keep the battery alive.

Frequently Asked Questions about F1 Active Aero 2026

Is Active Aero Automatic or Driver Controlled?

It is a mix of both. The activation of Straight Mode is done by the driver, who presses a button when they enter the allowed zones, similar to old DRS. The deactivation is often automatic; the wings snap back into Corner Mode (closed) as soon as the driver hits the brake or lifts off the throttle. This keeps the car from racing into a fast corner with a low-downforce setup by mistake.

Likewise, the car’s ECU handles most of the energy recovery (Recharge), but the driver still controls key tools like “Boost” and “Overtake.” The idea is that the driver makes the vital calls in big moments while the software looks after all the small, constant changes needed to keep the hybrid running well.

Does Active Aero Make Racing More Exciting?

The goal is to make racing feel more “real.” By taking away the simple DRS speed boost and replacing it with an energy-based fight, F1 wants overtakes that feel more earned. The smaller, lighter cars help too. With less size to manage, drivers can place their cars side by side more often, leading to braver moves through narrow parts of tracks like Baku, Singapore, and Monaco.

Because the car in front can also use Active Aero to cut drag, the chasing driver has to think harder to get by. That should lead to longer fights over several corners instead of the quick, single-zone passes that were common in the early 2020s. The excitement comes from not knowing exactly when and where a move will happen, and from seeing who uses their Boost better.

How Will F1 Police Active Aero Usage?

The FIA watches each car through a standard Electronic Control Unit (ECU). This sealed “black box” checks that teams only use Straight Mode in the legal zones and that Overtake Mode energy stays within the 0.5MJ limit. Any unusual power output or wing angle outside the rules shows up instantly in Race Control.

The FIA has also added “lap distance turn-offs” for Active Aero. This function closes the wings at a set point on the track even if the driver hasn’t braked yet. That stops drivers from trying to take a scary high-speed kink with the wings open, which could cause big accidents. This level of electronic oversight keeps the system fair and safe while F1 moves into this new era of racing.